Article 1 – Emancipatory SW theory and practice

Emancipatory Social Work Theory and Practice

by Professor Vishanthie Sewpaul (PhD)

(test recording of half of this chapter)

Emancipatory Social Work Theory and Practice has various roots in what has been called Conflict Theory; Critical Theory; Feminist Social Work Theory and Practice; Anti-Oppressive Theory and Practice; Anti-Racist Social Work; Structural Social Work Theory; Radical Social Work and Liberation Theology.

It must be noted that even within these categories there might be a broad range of leanings and dissenting views. For example, feminist theory has sub-divided into African feminism; Black feminism; Liberal feminism; Socialist feminism; Developmental feminism; Radical feminism; Lesbian feminism; Psychoanalytic feminism; and Cultural feminism.

As social scientists we fragment at our own peril! Liberation theology might take overt religious standpoints, such as Islamic Social Work; Buddhist Social Work or Christian Social Work, or be underscored by more unifying spiritual dimensions that address core values and principles, that are aligned with those of social work. Religions have the potential to oppress or to liberate; it is the liberation potential that emancipatory approaches embrace. What the various roots of emancipatory social work have in common is understanding the structural dimensions of life and power dynamics based on intersecting social criteria, and understanding and undoing oppression and/or privilege.

Emancipatory social work embraces these roots, but moves beyond them to focus on liberation from the constrains of one’s own thinking, recognizing the inter-connectedness between individual consciousness and societal consciousness, and the importance of transforming both individual and societal consciousness, directed towards deliberative, collective emancipatory action. Central to emancipatory social work is the politicization and awakening of the self, and the development of action strategies that such awakening provides the potential for.

Conventional social work, even with its more critical roots tends to focus on issues, problems and concerns of the people who social workers engage with. While not eschewing the importance of understanding, and heightening the consciousness of people who we engage with, and adopting participatory methodologies to engage people as active agents, emancipatory social work turns the spotlight on us, as professionals. The focus is on how the constraints of our own thinking, and the worldviews that we hold might influence our conceptualization of people, their life challenges, the methods and strategies that we choose to use, and the goals that we aspire towards.

At the heart of emancipatory social work is understanding the multiple sources of oppression and/or privilege and working towards more just societies.

Understanding oppression

Broadly, oppression refers to the subordination of some groups of persons by another – usually more dominant group of persons, and is based on intersectional social criteria such as such as “race”, sex/gender, class, sexuality, (dis)ability, age, religion, ethnicity, language and nationality. These criteria intersect to influence access to power, status and resources.

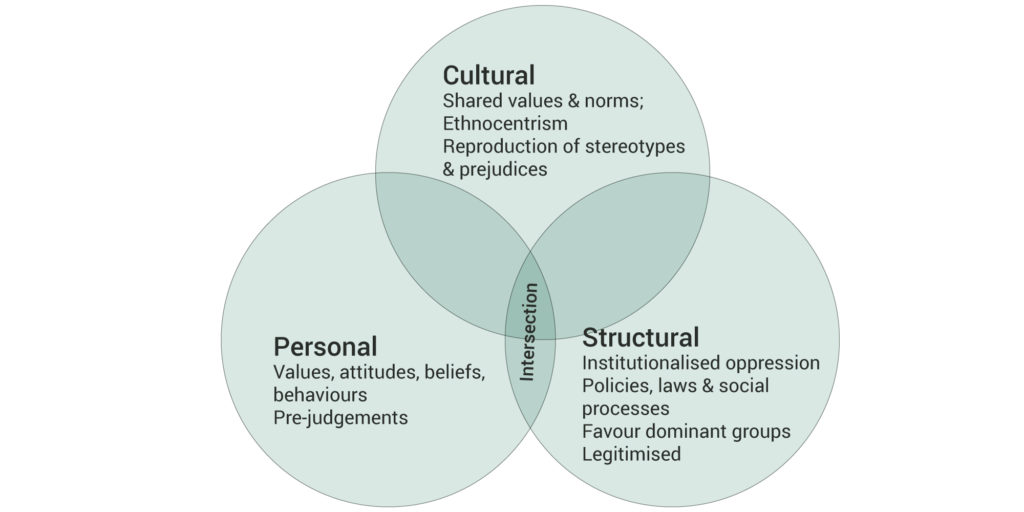

The relationship between the “oppressor” and the “oppressed” is a complex one, and the multifaceted dimensions of power must be considered. The dichotomy between oppressed and oppressor is often false, and oppression is often found within groups. People may also develop an attachment and fondness of their oppressors as discussed in Fanon’s (1970) thesis of loving the oppressor. Oppression, as reflected below is based on interlinking personal, cultural and structural factors (Mullaly, 1997).

The Awakening of Self and the Awakening of Society

The Global Social Work Statement of Ethical Principles (GSWSEP) (IASSW, 2018) emphasizes that the self must be the cite of awakening and politicization, and accepts a dialectal relationship between individual and societal consciousness. Asian beliefs and practices place a pre-eminence on self-liberation and enlightenment, as reflected in the Noble Eightfold Path i.e. righteousness of views, aspirations, speech, action, livelihood, effort, mindfulness and concentration (Nhat Hanh, 2018), and the yoga of synthesis (yoga meaning divine union) (Sri Swami Sivananda, 1979). The yoga of synthesis combines karma yoga (service and work made love in action); raja yoga (contemplation and meditation); jnana yoga (knowledge, discrimination, awareness and understanding); and bakthi yoga (the path of devotion) (Sewpaul, 1997). Of salience to social work is the skill of karma yoga, which is aimed at niskarma karma that teaches us to perform our work without attaching ourselves to the results of action. This is often erroneously taken to mean working without the expectation of a salary or reward. The Bhagavad Gita, Chapter 2, verse 47 says:

“Thy human right is for activity only, never for the resultant fruit of actions … neither allow thyself attachment to inactivity” (in Sri Paramahansa Yogananda, 1999 p. 281).

We have control only over actions in the current moment, not over the outcomes, yet we are often preoccupied with fears born out of past experiences or anxieties about the unknown future. The lesson is that if we dedicate ourselves 100%, unconditionally to the task/action at hand, the consequences will take care of themselves. For example, if a student commits himself or herself totally to the task of studying for an examination, rather than ruminate about the past or live in the future by trying to predict the content and outcomes of the examination, the desired results will be achieved. The overarching focus in Asian worldviews and practices is on mindfulness: living in the present; understanding the nature of the self and the universe, and their inter-relationships; and the non-permanence of all phenomena. The enlightenment derived from the understanding of the latter enables one to approach pleasure and pain; praise and criticism, and life’s sufferings with equanimity. If some of these worldviews and practices are infused into social work on a global level, they can contribute to a more enhanced profession.

The GSWSEP speaks of liberation from the entrapments of our own thinking. The GSWSEP, which applies to teaching, research and practice contexts, has specific principles related to this with 4.7 and 4.8 reading as:

Social workers recognize that dominant socio-political and cultural discourses and practices contribute to many taken-for-granted assumptions and entrapments of thinking, which manifest in the normalization and naturalization of a range of prejudices, oppressions, marginalizations, exploitation, violence and exclusions.

Social workers recognize that developing strategies to heighten critical consciousness that challenge and change taken-for-granted assumptions for ourselves and the people whom we engage with, forms the basis of everyday ethical, anti-oppressive practice.

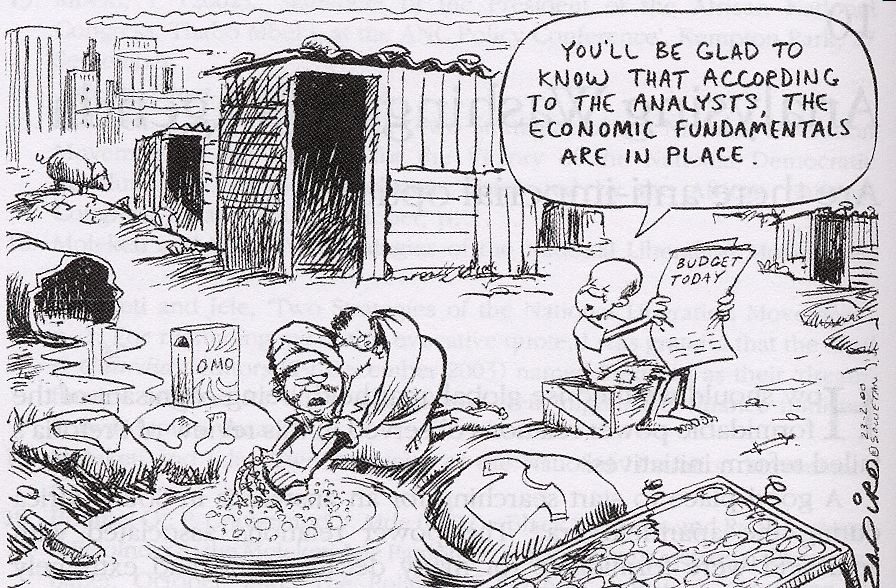

As social workers, we are products and producers of our socio-political, economic and cultural worlds. The ideologies that we hold are reflected in, and reinforced by, dominant social systems such as the family, education, culture, religion, economics, politics and the media (Sewpaul, 2013). It is, therefore, critical that we become aware of cultural, political and capitalist ideological hegemony and appreciate how we can shift from being the “subjected being” to a free subject that is the “author of and responsible for its actions” (Althusser, 1971, p. 182). With the development of self-awareness and critical consciousness (Freire, 1973) there is a greater chance that social workers would use their voice and skills to contribute to socio-economic, political and cultural change and development.

The self must become the site of awakening and politicization, and this must begin in the classroom (Sewpaul, 2013; 2015). Emancipatory social work is directed at heightening awareness of external sources of oppression and/or privilege that hold the possibility of increasing people’s self-esteem, courage and conviction, so that they, themselves begin to confront structural sources of poverty, inequality, marginalization, oppression and exclusion (Sewpaul and Larsen, 2014). Rather than the conventional outward focus on understanding people who we work with, the GSWSEP emphasizes that, as social workers, we need to begin with ourselves. Without transformation of our consciousness, we are not going to be able to transform societal consciousness. The systems, structures, laws and policies “out there” that we often criticize, are representations of the collectivities of consciousness of all of us, particularly of those who occupy powerful positions. We must be courageous enough to examine our complicities in reproducing the prejudices and harms that we wish to repudiate. Educators must provide safe spaces in the classroom to facilitate such self-examination, using strategies such as reflexive writing and dialogue, experiential teaching and learning, the biographies of students, journaling, art, drama and real world lessons.

Written for a global audience, the 2014 Global Definition and the GSWSEP do not address any specific religious and/or spiritual leanings. Some might interpret the empowerment and liberation that is referred to in the Global Definition from a pragmatic, secular point of view only, while others might combine this with understandings of liberation theologies.

The pedagogical and practice implications of principles 4.7 and 4.8 will be contextually interpreted and applied, as social work educators, researchers, practitioners and students adopt strategies that challenge and change ideological control of consciousness that are usually at the heart of prejudices, discriminations, oppressions, poverty and inequality based in inter-sectional social criteria such as race, caste, gender, class, sexuality, religion, language and geographic location (Sewpaul, 2013; Sewpaul and Larsen, 2014).

Buddha did this 2500 years ago: as he challenged the nobility and the religious and political elite to understand, and undo the structural sources of discriminations and injustices – based on social position and caste, and to some degree gender, and to use non-violence, loving kindness, care and compassion to bring about a more just and equal world (Nhat Hanh, 2018), thus highlighting the inextricable relationship between the personal and the political (Sewpaul, 2015).

Emancipatory Social Work Education: The Power of Biography

Gramsci (1977) saw the starting point of critical elaboration to be the positioning of oneself as a product of the historical process. In a similar vein, Giroux argued that an examination of the historical and social constructs of our lives “…helps to reterritorialize and rewrite the complex narratives that make up [our] lives” (Giroux, 1997:159). Critical and emancipatory pedagogy raises important issues regarding the way we construct our identities within particular historical, cultural and social relations, with the intention of contributing to a more democratic life. For bell hooks (1989), a feminist writer, one’s voice should be the object of theoretical and critical analysis so that it can be connected to broader notions of solidarity, struggle and politics. Apart from the personal-political identity links, the power of biography lies in its potential to reflect how power and/or powerlessness are reproduced in everyday life experiences. My personal biography confirms that emancipatory pedagogy begins with everyday life experiences and in particular the basis of learning, deconstruction and action.

“I experienced my most formative years as a child, adolescent and young adult in apartheid South Africa. Such was the power of the internalised oppression of my mother, that I grew up in a family setting where the status quo was completely accepted. Here we were made to believe that whites were demigods, to be respected and revered as such. My mother knew no better” (Sewpaul) . “Subjectivities are produced within those social forms in which people move but of which they are often only partially conscious” (Giroux, 1997:158, my emphasis). Thus, we become prisoners of our socio-cultural worlds; “the voluntary imprisonment of the free subject” (Sewpaul, 2013, p. 120).

“Widowed at a very young age, with me, the youngest of seven children – being five months old at the time of my father’s death through suicide, my mother worked as a domestic servant for whites for almost forty years. Hence her sense of gratitude for whites having provided her with a livelihood, or perhaps it was a reflection of Fanon’s (1970) thesis of loving the oppressor. Our subservience to whites was understandable, as the only relationship that we shared with them was one of “master” and “servant”. Group areas and separate amenities legislation ensured that we did not get to know whites in any other capacity, let alone as equals. Such was my mother’s indoctrination that, while walking on the streets where whites lived, we were shushed into silence as children because “whites don’t like noise”. Under such circumstances my capacity to externalise and to understand the sources of oppression and of my diminished sense of self (which was quite acute!) were clearly limited” . (Sewpaul)

At the height of apartheid there were innumerable laws such as the Separate Amenities Act, the Group Areas Act and the Immorality Act that were designed to inform people of colour that they were inferior. On reading signs that said “Whites Only” or “Right of Admission Reserved”, I did not see the problem as an aspect of an oppressive state, but rather I owned the problem and believed that something must have been wrong with me. Yet, I believe that I was more fortunate than most people of colour in South Africa. My experience would serve to confirm Giroux’s claim that the “…mechanisms of domination and the possible seeds of liberation reach into the very structure of the human psyche” (Giroux, 1983:39). The deeper the assaults of structural conditions on the psyches of people, the greater the chance that they will react against these.

In South Africa the discovery of Friere’s (1970, 1972, 1973) method of conscientisation through liberating dialogue and praxis came at just the right moment – during the 1970s when I was in secondary school. At this time Freire’s works, which were banned by the government, found their way into South African black universities and into the South African Student Organisation (SASO). His work, particularly the Pedagogy of the oppressed, had a profound impact on young activists of the Black Consciousness Movement (BCM) and contributed to the radicalisation and politicisation of education (Alexander, 1989). As a secondary school learner, I was fortunate to have had the guidance of black consciousness activists such as the late Steve Biko, Strini Moodley and his wife Sam Moodley. Sam entered our school as a young enthusiastic teacher bent on politicising us. She would get us engaged in fantasy trips, free writing and drama, replicating in the classroom the forces of apartheid and oppression. On picking up self-blame and messages of internalised oppression that were characteristic of so many of us, she would confront us with the realities and made us see that the real enemy was the apartheid state. The message “it is not your fault” was the turning point in my political awakening. Consciousness-raising strategies were coupled with further action in which as school learners we formed, with the help of the BCM leaders, a theatre group called the Chatsworth Arts and Theatre Organisation (CATO). Through CATO we undertook community political education, wrote Animal farm into a drama script and produced this as a play. These activities did not come without their own difficulties. Within weeks of CATO’s formation we had the Security Branch on us, with threats of suspension from school if we continued our political activities.

Apart from its intrinsic value in helping us recognise our own worth, the activities allowed us to gain a certain measure of control over our lives and over an unrelenting, oppressive system. This control in turn provided us with a sense of hope for change, an element emphasised by Giroux (1997) in Pedagogy and the politics of hope: Theory, culture and schooling. This hope was born out of some community initiatives, for example, successfully but non-violently resisting the authorities when they planned to terminate a vital bus transportation facility that would have severely jeopardised the livelihood of the working-class people in the area that we lived in. It is perhaps this kind of hope, and the vision of possible change among the generation of school and university learners, that culminated in the well-known 1976 Soweto Riots, where the slogan Liberation before education became popularised. In 1976, as a first-year university student in an ethnic institution that fully supported the apartheid status quo, we truly believed as we chanted that “we shall overcome someday.… black man [sic] shall be free someday”. The BCM, which was banned in 1977 provided an invaluable source of support, encouragement and guidance as we organised student boycotts and rallies. It is this background that informs my educational philosophy. Through these experiences and people such as Steve Biko, Strini and Sam Moodley, I realised that I was not a “…passive [victim] of society’s control elements” (Coetzee, 2001:137), and that I had the capacity to reflect and act upon these elements. This realisation informs my interactions with people, and my desired pedagogical, research and practice objectives, thus supporting the insights of bell hooks (1989), who argued that the value of the narrative lies in theorising experiences as part of a broader politics of engagement. I explore these in greater detail below.

On Friere, Gramsci and Giroux: Critical and Emancipatory Pedagogy

Having trained in an ethnically based “Indian” apartheid institution that was preoccupied with the reproduction of the dominant cultural and political ideology, with the majority of staff being white, I was certainly not introduced to any form of critical education during this period. As a secondary school learner, the benefits derived from critical consciousness and action, which allowed us to “…mobilize rather than destroy [our] hopes for the future” (Giroux, 1997:161), initially, as a young academic, led me to the work of Freire (1970, 1972, 1973) and later to the emancipatory pedagogies of Althusser (1971); Gramsci (1988, 1971, 1977) and Giroux (1983, 1994, 1997).

With reference to the central theses of Gramsci (1988, 1971, 1977) and Freire (1970, 1972, 1973), Giroux (1983) contended that the spirit of emancipatory/radical pedagogy is “…rooted in aversion to all forms of domination, and its challenge centres around the need to develop modes of critique fashioned in a theoretical discourse that mediates the possibility for social action and emancipatory transformation” (Giroux, 1983:2). Critical theorists believe in the dialectic of agency and structure, and developed theoretical perspectives that support the notion that history can be changed and provide potential for radical transformation. Giroux (1983, 1994, 1997), Gramsci (1971, 1977) and Freire (1970, 1972, 1973) addressed educational issues as political and cultural issues.

Paulo Friere, educator (1921 – 1997)

Writing in relation to the Brazilian people, Freire contended that “They could be helped to learn democracy through the exercise of democracy; for that knowledge, above all others, can only be assimilated experientially” (1973:36). Given the transition of Brazil from a closed to an open society at the time, Freire said in Education for critical consciousness:

“I was concerned to take advantage of that climate to attempt to rid our education of its wordiness, its lack of faith in the student and his [sic] power to discuss, to work, to create. Democracy and democratic education are founded on faith in men [sic], on the belief that they not only can but should discuss the problems of their country, of their continent, their world, their work, the problems of democracy itself. Education is an act of love, and thus an act of courage. It cannot fear the analysis of reality or, under pain of revealing itself as a farce, avoid creative discussion” (1973:36).

The value of Freire’s work lies in his linking micro-educational methodologies to theories of social change. This understanding, combined with his emphasis on te integrative processes of action, critical reflection, theoretical knowledge and participatory democracy, support the contention that the micro-macro dichotomy i a fallacious one. While the underlying assumption of Freire’s work is that critical understanding would lead to critical action, there is the possibility that his emphasis on egalitarian educator-learner relationships, and action and reflection, could become ends in themselves. However, as elucidated in my biography, Freire’s work had a profound impact on educational and political epistemologies in South Africa during the 1970s and 1980s. His writings provided the philosophical and methodological foundations for the positive engagement of students and of wider citizenship groups in the processes toward the struggle for democracy.

Central to Freirian pedagogy are dialogue and praxis – reflection in and on action – that take place in what Freire called cultural circles, where cultural animators/facilitators engage people in informal settings in small groups (Freire, 1973; Escobar and Escobar, 1981). In such settings all participants are educators and learners; the facilitator does not transmit or distribute knowledge as an objective intellectual or neutral expert. The cultural animator/facilitator engages with people so that all can understand a given reality. The animator’s role is primarily a political one where the dialogue is designed to uncover social realities, and to awaken critical consciousness aimed at transformation of a repressed and repressive society.

One way of achieving this is the use of generative words, codification and decodification (Freire, 1973; Escobar and Escobar, 1981). Groups choose generative words, which may be linked to pictures, photographs, sounds, the environment, etc, also called political alphebetization, for their sociological and political salience to critically describe and analyze situations that they find themselves in. Codification is “the intellectual representation of an existential situation” (Escobar and Escobar, 1981, p. 5) i.e. the meanings and concepts linked to the generative words. E.g. “race” might be the generative word, and the codification might include the overt and nuanced aspects of race; verbal and non-verbal dimensions; and visible and non-visible manifestations, to analyze the deep structures (e.g. of race and race thinking) within that which is tangible and visible – e.g. policies, laws, living conditions of people influenced by racism. Decodification involves a critical engagement with alphebitization and codification to engender critical consciousness, reconstruction and social change. The praxis supports making learning a part of the process of social change itself.

According to Freire (1973) “Dialogue requires social and political responsibility, it requires at least a minimum of transitive consciousness” (p. 21), which is paramount as Freire warned about the dangers of naïve consciousness, which can manifest in things like fanaticism, nostalgia or fatalism. In the words of Freire (1973):

A critically transitive consciousness is characterized by depth in the interpretation of problems; by the substitution of causal principles for magical explanations; by testing of one’s ‘findings’ and by openness to revision; by the attempt to avoid distortion when perceiving problems and to avoid preconceived notions when analyzing them; by refusing to transfer responsibility; by rejecting passive positions; by soundness of argumentation; by the practice of dialogue rather than polemics; by receptivity to the new for reasons beyond novelty and by the good sense not to reject the old just because it is old – by accepting what is valid in both old and new (p. 14).

Underscoring Friere’s (1973) approach is the importance of finding “solutions with the people and never for them or imposed upon them”, where people “enter the historical process critically” enabling them to reflect on themselves, their responsibilities and their roles; “indeed to reflect on the very power of reflection” (p. 13, highlights in original), which would increase their capacity to choose. These must be academia’s approach in our work with students, and social workers’ approach as they work with people in diverse settings.

Antonio Gramsci, philosopher and politician (1891-1937)

Similar to the thesis of Freire (1972, 1973), Gramsci (1977) argued that education should be used for the creation of a vision of the future through its daily practice, and that knowledge consists of theory and existential experience which is located historically within its context, and is based on action and reflection. Gramsci (1971, 1977) used the concept of hegemony as a central explanation of the functioning of the capitalist system, and elucidated the role of ideology and the state in the reproduction of class relations and in preventing the development of working-class consciousness. Gramsci went beyond Marxist economic determinism by expounding the ways in which common sense and identities are formed within their historical and social locations.

Central to Gramsci’s work is what he called common sense (also contradictory consciousness) and good sense. Gramsci claimed that “…all men [sic] are ‘philosophers’” (1971:323), with their philosophy contained in: (a) language, (b) “common sense” and “good sense”, and (c) the entire system of beliefs, superstitions, opinions and ways of seeing things and acting, which are collectively referred to as “folklore”. However, he contended that common sense functioned without benefit of critical interrogation. Common sense consists of the incoherent set of generally held assumptions and beliefs common to any given society, while good sense means practical, empirical common sense, thus the need to transform common sense into good sense. Contradictory consciousness or common sense is characterized by a dual conception of the world: “…one affirmed in words and the other displayed in effective action” (Gramsci, 1971:326). Thus, ideology is located not only at the level of language but also in lived experience. Gramsci saw the contrast between thought and action to be an expression of profounder contrasts of a socio-historical order. While social groups have their own conceptions of the world, such groups “…for reasons of submission and intellectual subordination” (Gramsci, 1971:237) have also adopted a conception which is not its own. In ordinary times, when such groups are not acting autonomously, it is the conception of the dominant group that prevails.

For Gramcsi (1971) the contradictory state of consciousness, characterized by innocuous ideologies, did not provide for choice and action, but for “moral and political passivity” (1971:333). Thus, in his Prison letters Gramsci wrote, “The outbreak of the World War has shown how ably the ruling classes and groups know how to exploit these apparently innocuous ideologies in order to set in motion the waves of public opinion” (1988:171). However, as Giroux pointed out, contradictory consciousness does not only point to domination and confusion, but also to “…a sphere of contradictions and tensions that is pregnant with possibilities for radical change” (1983:152).

Gramsci (1971) argued that innovation could not come from the masses, at least not at the beginning, except through mediation of the “elite” or the “intellectual”. The role of ideology becomes critical to the extent that it has the potential to reveal truths by deconstructing historically conditioned social forces, or it could reinforce the concealing function of common sense. It is thus vital that common sense be subject to critical interrogation. In Gramsci’s words: “Critical understanding of self takes place … through a struggle of political ‘hegemonies’ and of opposing directions.…Consciousness of being part of a particular hegemonic force (that is political consciousness) is the first stage towards a further progressive self-consciousness” (1971:333). Thus, the theory-practice nexus that arises with ideological critique and critical understanding is not merely a mechanical fact; it reflects the need for a historical consciousness. Historical consciousness, as a moment of ideological critique, functions “…to perceive the past in a way that [makes] the present visible as a revolutionary moment” (Buck-Morss cited in Giroux, 1997:84). Political revolutionary action for Gramsci (1971) could take the forms of war – a war of movement, a war of position and underground warfare. The war of position would constitute the passive revolution that takes place in societies characterized by relative stability.

Henry Giroux, scholar and founding theorist of cultural pedagogy (b. 1943 -)

Photo: Don Usner

Giroux embraces the central theses of Freire (1970, 1972, 1973) and Gramsci (1988, 1971, 1977) regarding politics, culture, class, education, critical consciousness and critical action, but he adds to his radical pedagogy significant issues of “race”, gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, multiculturalism, citizenship education and identity politics. Given social work’s current preoccupation with multiculturalism, Giroux’s views are worth mentioning. In what he called an insurgent multiculturalism, Giroux (1994, 1997) called for discourses on multiculturalism which have been used to victimize minority groups, with an emphasis on their deficits and one which presents them as the “other”, to be combined with discourses on power, racialized identities and class. In doing so, we need to move away from using white, which is a mark of racial and gender privilege, as a point of departure in identifying difference. Whiteness, as a “race” and colour, represents itself as an archetype for being civilized and good, and in so doing represents the Other as primitive and bad. This is characterized by the textured use of colour in the English language as a signifier for such archetypes. Thus all that is bad has become associated with black, such as black book, black sheep, blacklisted and blackmail. Would a deconstruction of “race” from the constraints of such representations mean a deconstruction of the very language that reproduces it; a language that has become embedded in the psyches of people to become, in Gramsci’s terms, the common sense?

Citing James Baldwin, Giroux claims that “…differences in power and privilege authorize who speaks, how fully, under what conditions, against what issues, for whom, and with what degree of consistent, institutionalized support” (1997:236). Critical multiculturalism must examine how racism in its various forms gets reproduced historically and institutionally, and essentialist views regarding black, female or African must be rejected. While multiculturalism generally focuses on the other, Giroux calls for a multiculturalism that provides “…dominant groups with the knowledge and histories to examine, acknowledge, and unlearn their own privilege” and to “…[deconstruct] the centres of colonial power and [undo] the master narratives of racism” (1997:236, emphasis mine). An insurgent multiculturalism brings into question not only the effects of racism in terms of the nihilism that permeates black communities and of poverty, unemployment, racist policing and so on, but the origins of racism in the historical, political, social and cultural dynamics of white supremacy. This proved to be invaluable in my engagement and reflection with the students.

Giroux (1997) contends that Gramsci’s thesis regarding ideological hegemony, as a form of control that manipulated consciousness and shaped daily experiences and behaviour, is crucial to our understanding of how cultural hegemony is used to reproduce economic and political power. Advanced industrialized countries like the United States distribute not only goods and services unequally, but varying forms of cultural capital – “…that system of meanings, abilities, language forms, and tastes that are directly and indirectly defined by dominant groups as socially legitimate” (Apple, cited in Giroux, 1997:6). Within the dominant culture, meaning becomes universalized, and historically conditioned processes and notions of social reality appear as self- evident, given and fixed. Thus, as Freire (1970, 1972, 1973) and Gramsci (1971, 1977) held, the importance of “…critical reflection lays bare the historically and socially sedimented values at work in the construction of knowledge, social relations and material practices” (Giroux, 1983:154).

Giroux contends that the modes of analysis in radical pedagogy must be underscored by two major questions: (a) how do we make education meaningful by making it critical; and (b) how do we make it critical so as to make it emancipatory (1983:3). Giroux (1983, 1997) attacks modernist, technical-positivist rationality, which elevates reason to an ontological status, arguing that it does not allow for subjectivity and critical thinking, and that it is antithetical to the development of citizenship education. He posits arguments for citizenship education to be informed by an emancipatory rationality, which is based on the principles of critique and action, and which reproduces and stresses the “…importance of social relationships in which men and women are treated as ends and not means” (Giroux, 1983:191).

Emancipatory citizenship education must be used to stimulate students’ passions and imaginations, so that they may be encouraged to challenge the social, political and economic forces that impact upon the lives of people; to display what Giroux (1983:201) called civic courage. Issues regarding citizenship and democracy cannot be addressed within the restrictive language of markets, profit, individualism, competition and choice, which create indifference to inequality, hunger, deprivation, exploitation and suffering. Educators must have moral courage and power of criticism, and must not, in the name of objectivity, distance themselves from power relations that exclude, oppress, subjugate, exploit and diminish other human beings. We need to create opportunities for the development of critical consciousness and, where possible, for transformative action. In striving to achieve these objectives we need to begin where the students are, within their historical and socio- cultural spaces, in the hope that students would transfer these into their practice contexts.

The Embodied Vulnerability of Humanity

Informed by emancipatory theory and praxis, the GSWSEP makes being for the Other (Bauman, 1993; Levinas, 1985; Sewpaul, 2015) the normative in social work. The potential asymmetrical nature of such relationships might bear the risk of minimizing and patronizing the Other in social work relationships. But the appeal for such an approach lies in the GSWSEP’s emphasis on inter-dependence, where one’s humanity is recognised in relationships with others, echoing the value of Ubuntu (Letseka, 2014) with the African maxim, “I am a person through other people”, or “I am because we are”, which is also reflected in other value systems across the world. Levinas (1985) and Bauman (1993) asserted that the moral self, accords the unique Other that priority assigned to the self. For Levinas, to be responsible means to make oneself available for service of the Other in such a way that one’s own life is intrinsically linked with that of others. This is reflected in the GSWSEP. The justification for the self begins with the Other; our responses to the call of the Other define ourselves. Thus, Bauman’s (1993) emphasis on meeting with the stranger – the Other as Face – not as persona, a mask worn to signify the role played.

The unconditional positive regard implied in the above inheres of spiritual beliefs of humankind, the dignity and infinite potential that every human being possesses, and the importance of differentiating between the person and her/his conduct, attitudes or circumstances that might be in need of change. Linked to this is Bergoffen’s argument (cited in Feder, 2014) that we must challenge “the traditional grounding of human rights in the principle of individual autonomy” to protect and privilege “the humanity of our embodied vulnerability” (p. 117). By virtue of being born into this world each one of is vulnerable. Of particular salience to social work is Bergoffen’s contention that dignity predicated on autonomy is a fantasy born of “a desire to escape the risks of being vulnerable”, and the importance of conceiving of human rights, not in a narrow sense of “inhering within individuals” but rights located “between” individuals (p. 179). In a similar way, Miller (2017) sees dignity foregrounded in relationality; the recognition that one’s humanity is only recognized in solidarity and inter-connectedness with the Other. No person is totally autonomous and independent; we are all interdependent. Intersectionality highlights various social criteria that render some persons/groups of persons more vulnerable than others, but we are all imbricated in socio-political and economic systems, socio-cultural conventions, and dominant societal discourses, thus rendering us all, even the most privileged of us, vulnerable to varying degrees.

Understanding the embodied vulnerability of humanity might: facilitate more empathetic tuning into the life worlds of people; minimize othering as ‘us’ versus ‘them’; counter the idea of the social worker as expert; contribute to more egalitarian relationships; and enable us to truly be for the Other. It is for these reasons, and the attempt to de-stigmatize social work services, that neither the 2014 Global Definition nor the GSWSEP uses the word “client”, but refers to people who we work or engage with. The GSWSEP acknowledges the complexities that our embodied vulnerabilities bring to the social work relationship, with Principle 1.3 reading as: “As social workers we (as do the people whom we engage with) bring to the working relationship our histories, pains and joys, values, and our religious, spiritual and cultural orientations. Critical reflection on how the personal influences the professional and vice versa must be the foundation of everyday ethical practice”. Thus, the need for the awakening of awareness and consciousness.

Critiques of emancipatory theory

One of the main criticisms is that it is too political. It bears the risk that focusing on collective action might be at the expense of individual’s immediate needs. The argument is that the social work mandate is to help people with the day-to-day problems, and not change the system. There is also the risk that in adopting such an approach, social workers can become

paternalistic (Hutchinson and Otedal, 2014). We must be mindful, as Humphries (1997) warned, we (as university students, educators, researchers and practitioners) are implicated in power, and that our very aspiration to liberate can reproduce patterns of dominance and subordination.

To avoid this: 1) Work with – not only for people; 2) Politicization and acute awareness of the Self; 3) Engage in individual and collective advocacy; 4) Embrace human rights and social justice at all levels.

The dynamics of internalized oppression: Race, gender, class/capitalist hegemony

Next: Case study and task

The dynamics of internalized oppression: Race, gender, class/capitalist hegemony

Case study

Leila is a 35-year-old woman from India who has been living in Norway for the past six years. She has 5 children (four girls and one boy): 13-year-old girl, Nimmi; 11-year-old Raj (boy); a 9-year-old Ragini; 7-year-old Rana; and 4-year-old, Rohini. Leila called the child welfare authorities saying that she was struggling and not coping with the children. She has been divorced for four years. Her ex-husband provided, erratically, for the children in the past. One year ago he returned to India and has since stopped providing any financial assistance. She has been working part-time, about 20 hours per week, as a housemaid, for different people. Leila indicated that she is very concerned about Nimmi who started going out with friends and has twice come home very late. When Leila told her this is not how children in India behave, Nimmi said: “Well we are not in India, you brought me here. Get used to it.” Leila indicated that such back-chatting and behavior cannot be tolerated, and on the two occasions when Nimmi came home late, she slapped her. When the social worker told her this was unacceptable Leila looked at her wide-eyed. A few times when the social worker visited she noted that Leila’s aunt and uncle and their four children were at home with Leila’s children and that Leila was not at home. In a subsequent visit, the social worker told Leila that they would be placing the girls in a children’s home and that Raj would go to a Norwegian visiting-home, with a “positive” and “resourceful” family, on weekends. To this Leila lowered her voice and almost in a whisper said: “But I will try to be like a good Norwegian mother.”

The children were unhappy about this. The visiting-home family reported concerns about Raj; he was withdrawn and did not talk to the family. He expressed little emotions and was having difficulty at school.

While some of the details of the case have been changed, this is an actual recording of the social worker*:

In the boy’s home the family sits on the floor when they eat and the apartment is hardly furnished. The visiting-home is a beautiful home according to Norwegian standards. The Norwegian family is engaged in aesthetics and cultural values. In the boy’s home, food is just a necessity, whereas in the visiting-home meals are shared, planned and enjoyed. In the boy’s home they do speak Norwegian, whereas in the visiting-home they are all very social and love having conversations. The boy is occupied with after-school activities but is not guided by his mother. The visiting-home, on the other hand, wishes to offer activities they find developing and also offer to be there to guide him both physically and mentally. In his home… he does not have his own room; he has no space for himself. He seems insecure and scared when he is alone in his room in his visiting-home. In his home there are lots of different people that come and go – aunts, uncles and others. In the visiting-home they are engaged in life as a nuclear family, but they meet with other families at planned activities.

* See Ylvisaker, S. and Rugkasa, M. and Eide, K. (2015). Silenced stories of social work with minority ethnic families in Norway, Critical and Radical Social Work, 3 (2): 221-36.

Write an analysis of the above case using primarily emancipatory theory. Supplement your analysis by indicating how systems theory would add to your assessment and interventions.

References

Alexander, N. 1989. Liberation pedagogy in the South African context. In: CRITICOS, C. (ed) Experiential learning in formal and non-formal education. Durban: Media Resource Centre, Department of Education, UND.

Althusser L. (1971) Ideology and ideological state apparatuses. In: Althuser L (ed) Lenin and philosophy, and other essays. London: New Left Books, 127-188.

Bauman Z. (1993) Postmodern ethics, Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing.

Coetzee, J.K. 2001. A micro foundation for development thinking. In: COETZEE, J.K. et al. (eds) Development: Theory, policy and practice. Cape Town: Oxford University Press.

Escobar, H. and Escobar, M. (1981). Dialogue in the pedagogical praxis of Paulo Freire. Geneva: World Council of Churches.

Fanon, F. 1970. The wretched of the earth. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Feder E. K. (2014) Making sense of intersex: Changing ethical perspectives in biomedicine, Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Freire, P. 1970. The pedagogy of the oppressed. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Freire, P. 1972. Cultural action for freedom. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Freire P. 1973. Education for critical consciousness. New York: The Seabury Press.

Giroux, H.A. 1983. Theory and resistance in education: A pedagogy for the opposition.

London: Heinemann Educational Books.

Giroux, H.A. 1994. Living dangerously: Identity politics and the new cultural racism. In: Giroux, H.A. & McLaren, P. (eds) Between borders: Pedagogy and the politics of cultural studies. New York: Routledge.

Giroux, H.A. 1997. Pedagogy and the politics of hope: Theory, culture and schooling.

Colorado: Westview Press.

Gramsci, A. 1971. Selections from the prison notebooks (ed & transl by HOARE, A. & SMITH, G.N.). London: Lawrence & Wishart.

Gramsci, A. 1977. Selections from political writings 1910-1920. London: Lawrence & Wishart.

Gramsci, A. 1988. Gramsci’s prison letters (transl by Henderson, H.). Edinburgh: Zwan Publications.

Hooks, B. 1989. Talking back. Boston: South End.

Hutchinson, G. S. and Otedal, S. (2014). Five theories in social work. Universitet 1, Nordland.

Humphries, B. (1997). From critical thought to emancipatory action: Contradictory research goals? Sociological Research Online, 2 (1): http://www.socresonline-otg.uk/2/1/3.html

International Association of Schools of Social Work and International Federation of Social Work. (2014) Global definition of social work. Available at: http://www.iassw-aiets.org/uploads/file/20140303_IASSW%20Website-SW%20DEFINITION%20approved%20IA

International Association of Schools of Social Work. (2018) Global Social Work Statement of Ethical Principles. Available at: https://www.iassw-aiets.org/2018/04/18/global-social-work-statement-of-ethical-principles-iassw/.

Letseka M. (2014) Ubuntu and justice as fairness. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 5(9): 544-551.

Levinas E. (1985) Ethics and infinity, Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press.

Miller S. C. (2017) Reconsidering dignity relationally. Ethics and Social Welfare 11(2): 108-121.

Mullaly, R. P. (1997). Structural social work: Ideology, theory and practice. Oxford University Press.

Nhat Hanh T. (2018) Old path white clouds: Walking in the footsteps of the Buddha. New Delhi, Full Circle Books.

Sewpaul V. (2013) Inscribed in our blood: Confronting and challenging the ideology of sexism and racism. Affilia 28(2): 116-125.

Sewpaul V. (2015) Politics with soul: Social work and the legacy of Nelson Mandela. International Social Work, DOI: 10.1177/ 0020872815594226.

Sewpaul V and Larsen, A.K. (2014) Community development: Towards an integrated emancipatory framework, In (eds.) Larsen, A.K; Sewpaul, V. and Oline, G. Participation in Community Work: International Perspectives, London: Routledge.

Sri Parahamsa Yogananda (1999) God talks with Arjuna: The Bhagavad Gita. California: The Self-Realization Fellowship.

Sri Swami Sivananda (1979) Fourteen lessons on raja yoga. Rishikesh: Divine Life Society.

Downloadable files

Here we can put a link to .pdf version of the article or associated downloadable resources ![]()