Article – Systems and Ecological-Systems Theory

Systems and Ecological-Systems theory

by Professor Vishanthie Sewpaul (PhD)

Introduction

General systems theory is largely attributed to the seminal work of the biologist, Ludwig von Bertalanffy, and is said to have its genesis in the 1930s and 1940s. Von Bertalanffy countered the view of the world as chaos and a product of chance, and proposed that the world be conceptualized as organization and inter-dependence. Nothing can be explained in isolation (Lilienfeld, 1978). Von Bertalanffy (1968) wrote about “systems of various orders not understandable by investigation of their respective parts is isolation”, unlike in the past where “science tried to explain observable phenomena by reducing them to an interplay of elementary units investigable independently of each other” (pp. 36-37).

Von Bertalanffy (1968) identified the following as the central aims of general systems theory:

- There is a general tendency towards integration in the various sciences, natural and social.

- Such integration seems to be centred in a general theory of systems.

- Such theory may be an important means for aiming at exact theory in the nonphysical fields of science.

- Developing unifying principles running ‘vertically’ through the universe of the individual sciences, this theory brings us nearer to the goal of unity in science.

- This can lead to a much-needed integration in scientific education (p. 38).

In elucidating the above aims, Von Bertalanffy (1968) raised the debate around scientific generalization and scientific specialization, with the latter viewing “the world and all that it contains (as) an assembly of small and distinct parts” while systems theory views the world as irreducible, integrated and inter-related (Laszlo and Krippner, 1998, p. 57). Laszlo and Krippner (1998) concluded that the systems approach is “not an alternative, but a complement, to the specialized way. It is more all-embracing and comprehensive, incorporating the specialized perspective as one aspect of a general conception” (p. 57). This has salience for social work, which often embraces various areas of specialization within a generalist systems theoretical framework, and it underscores the importance of inter-disciplinary and inter-sectoral collaboration.

One of the key thrusts of general systems theory was to challenge disciplinary parochialism, with Von Bertalanffy (1968) arguing that “the physicist, the biologist, the psychologist and the social scientist are, so to speak, encapsulated in their private universes, and it is difficult to get word from one cocoon to the other” (p. 23).

Interestingly, Von Bertalanffy (1968) acknowledged that the idea of systems was nothing new. Asian philosophies reflect that it has an over 2500-year history.

The Buddha, for example, was perhaps one of the first systems theorists, while he did not label his work and teachings as such. There is the Buddhist teaching on dependent or inter-dependent co-rising; the complex chains of inter-dependencies in all phenomena and in existence and non-existence (Nhat Hanh, 1999; 2018). Buddha told his followers, “When you look at a leaf or a raindrop, meditate on all the conditions, near and distant, that have contributed to the presence of that leaf and raindrop. Know that the world is woven of inter-connected threads. This is, because that is. This is not, because that is not”, and taught that we be able to see the whole of the universe in every phenomenon; in a single leaf and in the self (cited in Nhat Hanh, 2018, p. 409). This supports the view that “the natural and human-made universe do not come in neat disciplinary packages labelled scientific, humanistic, and transcendental; they invariably involve complex combinations of fields” (Laszlo and Krippner, 1997, p. 50).

While systems theory has its origins in organismic biology, it has come to influence many disciplines across the the natural sciences and the humanities and the social sciences, including social work and psychology.

Systems theory presumes that there are universal principles of organization, and has thus come to be known as a grand theory, which post-modern and post-structuralist thinkers such as Foucault (1972) and Leonard (1997) warn against. Laszlo and Krippner (1998) caution that “the line that separates the aspects of a system from those of its environment tends to blur as the unit of observation moves from natural and designed physical systems to human and conceptual social systems.

While the former are easier to define and have relatively clear-cut aims or purposes, the latter are more difficult to define; most often they do not have clear-cut and agreed upon aims or purpose, and even when agreed upon, these may change over time” (p. 48). The boundaries and the boundary maintaining functions of natural systems, are easier to identify and define than those of human and social systems, with the relationships and communication between human beings and their social contexts being characterized by complexity (Healy, 2014).

In the field of sociology, the genesis of systems theory is attributed to Talcott Parsons, who identified four universal functional aspects of systems: adaptation, goal attainment, integration and pattern maintenance (Parsons, 1977) and Niklas Luhmann, who conceived of systems in terms of complexity difference in relation to the environment; the system’s attribution of meaning to communication and thus the option to select among plural alternatives; and systems as specializing in fulfilling singular functional needs, e.g. functional systems in relation to economics, politics, religion, family (Luhmann, 1995).

Test yourself with the following question:

|

About Talcott Parsens |

Ecological-systems theory: Definition and foci

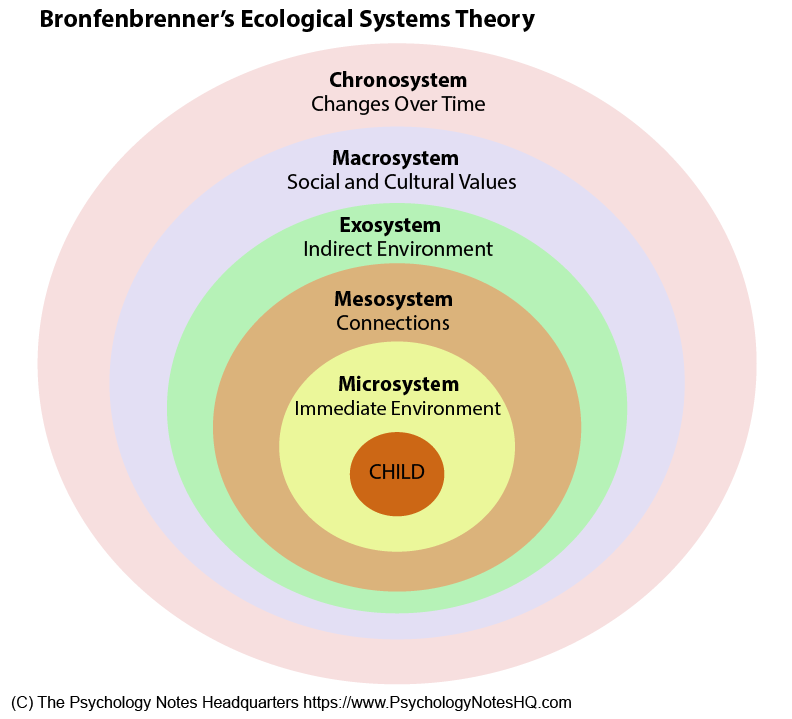

Bronfenbrenner (1979; 1997) expanded systems theory into an ecological-systems theoretical approach, which has marked influence on social work’s conceptualization of social issues (Gitterman and Germain, 2008; Hutchinson and Otedal, 2014; Siporin, 1080; Teater, 2014). The over-riding emphasis of ecological-systems theory is on development-in-context, and person-in-context.

A system is a “complex of interacting components together with the relationships among them that permit the identification of a boundary maintaining entity or process” (Laszlo and Krippner, 1997, p. 57). A system may be conceptualized an organized whole made up of inter-related and inter-dependent parts, in which the whole is more than the sum of its parts.

Given the above definition with its emphasis on “organized whole” a group of unrelated people who happen to be travelling together on a train or bus do not constitute a system in that they are neither inter-related or inter-dependent. As passengers they rely on an organized transportation system or network. The common denominator of being random passengers together does not qualify as a system.

The family is a good example of a system at the micro level, which has sub-systems (smaller units within the system) e.g. the parental sub-system and the sibling sub-system that are inter-related and inter-dependent, with inter-relationships within these sub-systems. Any change in one part of the system or sub-system will influence other parts of the system. Systems are characterized by purposeful and goal-directed activities, but these – as related to socio-cultural systems – can be very complex and conflicting, and change over time.

The “more than the sum of its parts” refers to the fact systems are characterized by patterned relationships amongst the various elements. E.g. the human body, as a system, is not a haphazard collection of its different organs – each of the organs function in coordinated ways to attain the purpose of maintaining health. The same applies to socio-cultural systems. From the micro level of the family to the macro level of large, complex organizations, each element in the system depends on the other, calling for complementarity of roles and open and clear communication. The “more than the sum of its parts” supports that while two socio-cultural systems, such as the family may be identical in structure, e.g. mother, father and two children of the same gender, the qualitative aspects of the family; its culture, modes of communication and expression and so on may differ markedly.

The larger systems that surround a system are called supra-systems. For example, the family is surrounded by religious, educational, economic, labour market, legal and cultural systems at different levels.

All of these influence the individual and family in profound ways. The relationship is a circular and dialectical one as the individual and family also influence and shape the systems around it. Relationships are bi-directional.

There are several foci to ecological-systems theory:

- Individuals interaction with and their influence on the environment, including the family environment and beyond.

- The influence of broader systems on individual and family development and functioning.

- The influence of the family, as a system, on the individual (a complex biopsychosocial, spiritual being) across the developmental life-span.

- The influence that individuals/families/groups have on each other within and across systems

Systems theory provides useful concepts to lend order to our relatively untidy and very complex world. It models “complex interpersonal, interpersonal, inter-group, and human/nature interactions without reducing perceptual phenomena to the level of individual stimuli” (Laszlo and Krippner, 1998, p. 53) supporting the notion that one’s perceptions, experiences and thinking are linked with structural conditions.

Ecological-systems: Key concepts

Reproduced from: https://www.psychologynoteshq.com/bronfenbrenner-ecological-theory/

The micro system “is a pattern of activities, roles, and institutional relations experienced by the developing person in a given setting with particular physical and material characteristics” (Bronfenbrenner, 1979, p. 22). It refers to the smallest unit of assessment and intervention, and includes the the individual, family, day-care, school, work in which the person directly interacts. In working at the micro level social workers are more likely to engage people in counselling, therapy, and provide material assistance and referrals. The reference to “experienced” by the person, refers to the fact that it is not only the objective properties of the setting that influence development; the individual’s subjective meanings attached to situations are just as important, reflecting an alignment with phenomenological and social constructivist approaches.

Meso/mezzo system – involves interactions between and across the various micro systems e.g. a parent’s engagement with schools, hospitals, associations, self-help groups. Assessment and interventions might rest at the level of micro systems, or they might include group and community based interventions in recognition of the interdependencies across the various systems.

Exo-system – does not involve the developing person as an active participant but has profound influences. E.g. parents’ flexibility of work hours; maternity & paternity leave; and medical insurance do influence the development of a child.

Macro-system – refers to “consistencies, in the form and content of lower-order systems (micro, meso, and exo) that exist, or could exist, at the level of the subculture or the culture as a whole, along with any belief systems or ideology underlying such consistencies” (Bronfenbrenner, 1979, p. 26). While the welfare state of Norway, e.g. reflects consistency at any given time in terms of laws and regulations, how these play out in the lives of individuals and families may vary a great deal. Macro systems are larger or supra systems that surround smaller systems. The blueprints of these macro systems manifest in ways where “homes, day care centres, neighborhoods, work settings, and the relations between them are not the same for well-to-do families as for the poor” (Bronfenbrenner, 1979, p. 26). Interventions at this level might include macro level strategies such as policy formulations and change, advocacy and lobbying.

Chronosystem – provides for an historical dimension of people’s development. A useful tool is the time-line. This allows for the charting of what Bronfenbrenner (1979) called “ecological transitions” i.e. “shifts in role or setting which occur throughout the life span” (p. 6).

Homeostasis – processes and mechanisms used by systems to maintain a relatively steady state.

Equilibrium – when the system has reached a state of balance.

Equifinality – a system may achieve the same results from different initial conditions and by various means.

Boundaries are “the repeatedly occurring patterns of behavior that characterize the relationships within a system and give that system a particular identity” (Zastrow and Kirst-Ashman, 2001, p. 5); it also characterizes relationships across systems and reflect and influence the amount of energy (information, resources & people) exchanged within and between systems. All boundaries according to Von Bertalanffy (1968) are “ultimately dynamic … and is never completely fixed” (p. 116). Closed, open and diffused boundaries have been widely used in social work, particularly in the field of family therapy. Closed or relatively closed boundaries (there is no such thing as a fully closed boundary) are generally associated with disengaged relationships; open boundaries with appropriate relationships and clear communication; and diffused boundaries with over-involved, inappropriate and enmeshed relationships. There are plenty of examples on the Internet about the use and application of these concepts with genograms and ecomaps, and symbols used to represent different types of relationships. Ann Hartman made the initial contributions to this. See e.g.

Hartman Diagrammatic Assessment of Family Relationships.pdf

Exchange – interaction between systems through which resources are shared. Resources or information into systems are called inputs, which are processed and used to produce outputs.

Network – patterned relationships between systems – regular exchange of inputs and outputs – can facilitate coordination and maximum use of resources

Status – one’s actual position in society

Role – dynamic aspect of status i.e. how one enacts or fulfils one’s position.

The ecological-systems approach has been used to understand the inter-relationship between humans, social systems and the natural geographic environment in relation to contemporary concerns around global warming and climate change, in what is called green social work (Dominelli, 2012).

The biomedical and the holistic biopsychosocial, spiritual systems approaches

In considering the individual as a system, and a complex, whole being we adopt a holistic biopsychosocial, spiritual (health) perspective as opposed to a narrow biomedical approach. The disease or biomedical model is premised in on a linear, reductionist, positivist conceptualization of phenomena (A causes B and therefore intervention C will produce result D), on the notion of the practitioner as a detached, neutral expert who makes a “diagnosis” and determines the “prognosis”, and the person as passive receiver of “treatment” provided. While this might seem absurd, it has unfortunately become infused into social work thinking over the years, with the inordinate influence of psychiatry on the profession, and the so-called “scientific” casework approach of Mary Richmond, who in 1917, in trying to emulate the medical profession published “Social Diagnosis”, in an effort to grant legitimacy to social work as a profession.

The holistic biopsychosocial, spiritual (BPSS) approach, which is reflected in the IASSW/IFSW (2014) Global Social Work Definition and the IASSW (2018) Global Social Work Statement of Ethical Principles (GSWSEP), underscores the importance of holistic assessments and interventions, social indicators of disease and illness and the importance of inter-disciplinary collaboration in dealing with the complexities of human development and human suffering. Linked to systems theory, the BPSS approach calls for an understanding of multiple and circular causality, not linear, and thus for assessments and interventions at multiple system levels, which is core to generalist social work practice.

The BPSS approach makes a meaningful differentiation between illness and disease. Illness is what a person experiences as symptoms and suffering and the meanings attributed to these, whereas disease is the underlying biological pathology. A person may have underlying pathology, without any experience of symptoms, just as a person may experience illness without any underlying pathology. Medical practitioners are usually preoccupied with disease, whereas people are more concerned with their personal experiences of distress and suffering (Kleinmann, 1988; 1998). Authur Kleinmann, whose treatise on human suffering bears much relevance for social work, exhorts us to see the bigger picture when dealing with human phenomena, including mental illness. In his words: “Here is where fear and aspiration, desire and obligation, mesh in the close encounters of ordinary men and women with the pain and disaster and with the infrapolitics of power that apportion those threats unequally and distribute responses to them unfairly across social fault lines in actual worlds” (Kleinman, 1998, p. 376).

Development within an eco-systemic and holistic BPS, spiritual framework

Human development is referred to as “the progressive mutual accommodation between an active growing human being and the changing properties of the immediate settings in which the developing person lives, as this process is affected by relations between these settings and by the larger context in which these settings are embedded” (Bronfenbrenner, 1979, p 21).

Critical features of this definition (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Berk, 2001)

- Developing person is not viewed as a tabula rasa i.e. blank slate as John Locke proposed. The developing person is a growing dynamic entity that progressively moves into and restructures the environment in which she/he resides.

- The environment also exerts its influence, requiring a process of mutual accommodation. Thus, the interaction between the person and the environment is characterized by reciprocity and bi-directionality.

- The environment is not restricted to a single immediate setting e.g. the family. Conceived as of a nested arrangement of concentric structures, each layer of the environment is contained within the next.

- Development as lifelong – no one phase is more important than another; not as deterministic as e.g. Freud’s psycho-sexual and Erickson’s epigenetic theories.

- Development at multi-directional – life is characterized by periods of growth and decline, and gains and losses.

- Development as plastic – human beings are open to change and to new experiences throughout the life-span.

- Development as embodied in multiple contexts: Age-graded influences (impact of chronological age on development e.g. normative expectations related to age); History-graded influences (cohort influences –g. South Africans experiencing apartheid and transition to democracy; contemporary technology-driven societies) and Non-normative influences – illness and sudden death, earthquakes, floods, involuntary childlessness.

Critiques of systems theory

With its origins in organismic biology, systems theory underscores the importance of systems striving towards homeostasis and equilibrium. This has placed an inordinate emphasis on the adaptation and coping discourse – that individuals must adapt to and cope with adverse life circumstances. System-maintenance approaches and functions, which have come to permeate social work and social policy, has been widely criticized. Sewpaul (2005) critiqued South Africa’s 2005 proposed Family Policy (Department of Social Development [DSD], 2005), which adopted a conservative, judgmental, personal-deficiency, and residual approach to family living. The Policy began with a situational analysis, which read as follows:

In the second decade of democracy, South Africans continue to suffer the ravages of an oppressive and exploitative legacy. The long-term effects of apartheid, migrant labour, land displacement, rapid urbanization, and poor rural development, amongst others, may require no less than a generation to redress.

Add to this widespread poverty, escalating incidences of HIV infection and AIDS, rampant domestic violence and rape, growing sexual abuse of children, and increasing crime and drug trafficking, and hope for the future becomes even bleaker.

Incredulously, the above was immediately followed by: “In all of this the Family remains the crux of how South Africans cope – or fail to cope – in a society challenged with rebuilding the moral fibre within individuals and amongst communities (DSD: 2005, p. 6, emphasis mine). The document made 10 additional calls for the moral regeneration of individuals and communities. Sewpaul (2005) pointed out that there were two obvious problems reflected in the document. Firstly, the burden of coping with South Africa’s huge problems is reduced to the level of individuals and families, without recognition of the structural sources of unemployment, economic oppression and exclusions, inequality and poverty on people’s lives, and the profound roles that society and State play in contributing to the way that families cope. Secondly, rebuilding the moral fibre of individuals and communities was seen to be the panacea for all the problems mentioned. The Family Policy speaks to “the value of self-reliance over dependency and learned helplessnes… The family should restore its pride and dignity in order to reverse dependency and the displacement of family responsibility” (DSD, 2005, p. 55, emphasis mine). The text reflects a conservative, neoliberal appropriation of language to justify abdication of state responsibility towards families, reflects a “goodness of fit” approach, and calls for families to adapt to and cope with conditions that they have no control over. Sewpaul (2005) concluded her critique of the Family Policy by posing the following question: If external socio-economic, political and cultural factors are maintaining families in poor, dispossessed and helpless positions, how are such families expected to move toward independence and self-reliance within the same structural constraints? (p. 9).

Systems theory emphasis on homeostasis and equilibrium has minimized recognition that disequilibrium may be a necessary precursor to gain and positive change. On the other hand, in Pincus and Minahan’s systems approach, the conception of the social worker as “change agent”, bears the risk of change itself being seen as the goal, which might detract from the actual needs and problems of people (Hutchinson and Otedal, 2014).

As a grand narrative, systems theory is seen to be too ambitious, with some assuming that a single profession can be all things to all people (Hutchinson and Otedal, 2014). Also the theory focuses on how society is. Questions around aesthetics, morality, ethics, how society “ought to be” do not feature. At best, the theory has a “weak focus on morals and ethics”; there is “no stand taken and conflicts of interests are not identified” (Hutchinson and Otedal, 2014, p. 222).

The theory does not focus on power relations in society, and places no moral imperative on the part of the social worker to challenge and undo oppression, poverty, inequality, exclusion and marginalization, which are almost always linked to intersecting social criteria such as race, class, gender, sexual orientation, nationality, age, (dis)ability and nationality.

References

Berk, L. E. (2001). Development through the lifespan. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1997). The ecology of developmental processes. In R. M. Lerner (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Theoretical models of human development. New York: Wiley.

Department of Social Development (2005). Draft national family policy. Pretoria: Department of Social Development.

Dominelli, L. (2012). Green social work: From environmental crises to environmental justice. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Gitterman, A. and Germain, C. B. (2008). A life model of social work practice: Advances in theory and practice. New York: Columbia University Press.

Healy, K. (2014). Social Work theories in Context. Creating a framework for practice. 2nd

Ed. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Foucault, M. (1972). The archeology of knowledge. New York: Pantheon.

Hutchinson, G. S. and Otedal, S. (2014). Five theories in social work. Universitet 1, Nordland.

International Association of Schools of Social Work and International Federation of Social Work. (2014) Global definition of social work. Available at: http://www.iassw-aiets.org/uploads/file/20140303_IASSW%20Website-SW%20DEFINITION%20approved%20IASSW%20Board%2021%20Jan%202014.pdf.

International Association of Schools of Social Work. (2018) Global Social Work Statement of Ethical Principles. Available at: https://www.iassw-aiets.org/2018/04/18/global-social-work-statement-of-ethical-principles-iassw/.

Kleinman, A. (1988). The illness narratives: suffering, healing, and the human condition. New York: Basic Books.

Kleinman, A. (1998). Experience and its moral modes: Culture, human conditions, and disorder. The Tanner lectures on human values. Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA. 13-16 April.

Laszlo, A. and Krippner, S. (1998). Systems theories: Their origins, foundations, and development. In (ed). J. S. Jordan, Systems theories and a priori aspects of perception. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science.

Leonard, P. (1997). Postmodern welfare: Reconstructing an emancipatory project. London: Sage Publications.

Lilienfeld, R. (1978). The rise of systems theory: An ideological analysis. New York: Wiley

Nhat Hanh, T. (1999). The heart of the Buddha’s teaching: Transforming suffering into peace, joy and liberation. London, Random Books.

Nhat Hanh T. (2018) Old path white clouds: Walking in the footsteps of the Buddha. New Delhi, Full Circle Books.

Richmond, M. (1917). Social diagnosis. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Sewpaul, V. (2005). A structural social justice approach to family policy: A critique of the Draft South African Family Policy. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk. 41(4): 310-322.

Siporin, M. (1980). Ecological systems theory in social work. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 133: 133-142.

Teater, B. (2014). Social work practice from an ecological perspective. In C.W. LeCroy (Ed.), Case studies in social work practice. (3rd ed.). Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Von Bertalanffy, L. (1968). General systems theory: Foundations, development, applications. New York: George Braziller.

Zastrow, C. and Kirst-Ashman, K. K. (2001). Understanding human behavior and the social environment. Belmont, CA: Brooks Cole/Thomson Learning

Case Study: Deidre

Illustrasjonsfoto

Deidre is a 42-year-old woman with three children; Maria aged 15; Yuri, aged 11 and Jean, aged 10 years. She was in a relationship with Thomas since 2002 when she left Romania and came to live in Finland. They were married in 2003. Maria was born of a prior relationship in Romania. Thomas was previously married with two children from that relationship.

Deidre is a medical doctor and Thomas has his own business in construction, putting insolation in buildings. Deidre has reported to the police being physically abused by Thomas and has medical evidence about this. At the time, Deidre could not speak Finnish and when questioned by authorities, her husband would answer on her behalf. On learning Finnish and reading some of the recordings, she found that Thomas misrepresented their domestic situation and accused her of being an unfit mother. The couple divorced in 2015. At that time the children were placed in the custody of Deidre.

In 2016 her ex-husband took her to court with the charge being Deidre “turning the children against him”, as the children did not want to visit and spend time with him. The court found her guilty and she had to pay a fine of 10 000 Euros. The children, Yuri and Jean, were removed and placed in the custody of the father. However, they were very unhappy and the father did not provide the required care. The children were subsequently taken into care and placed in two different children’s home. The reason given for this was that Yuri would influence Jean. They are very unhappy and want to be with the mother, and the mother is desperate to have the children with her. When the father comes to visit at the children’s home, Jean hides under the bed and refuses to see him. The social workers refuse to let the children go home, saying that the mother is manipulative and responsible for alienating the children from the father, and they say that the children are “too close to the mother”. The main reason for this being that the children sometimes take turns sharing the bed with the mother. The mother has reverted to the Rumanian Embassy in Finland and the European court for assistance.

Write an analysis of the above case using primarily systems theory in your assessment and interventions. How might critical, emancipatory theory assist you with enhanced understanding and intervention?

Watch this YouTube film which shows how the children were removed from their home:

Case 2

Illustrasjonsfoto

A 49-year-old woman presents with major depressive symptoms, which she has been experiencing over the past two months. She is hypertensive (i.e. has high blood pressure) and complains of backaches. She received up to primary school education, as her parents, who had limited financial means, believed that it was more worthwhile to invest in their three sons, as girls are “passers-by” who would get married and leave home. She has never worked outside the home. She says that she feels “useless” as she does not contribute to the family upkeep, and her husband has, every now and again, told her that she would never make it on her own. She has a long-standing history of marital difficulties, and was beaten up on three occasions. Six months ago she learned that her husband was having an extra-marital affair, and three months ago her youngest son left home to go to college. She has always been a quiet, unassertive person who has had difficulties making life decisions. She believes that her current circumstance is part of her destiny in life and that she has little power or control over it.